Guardian of Her Memory

or

Don’t Forget the Ponagation

If someone you loved were murdered, you would understand what a contradiction of emotions ensues when the horror of her death is her memory. It hurts. Nothing could be more wrong. I am attempting to right a wrong. Her memory should be sweet, because that’s who my mom, Helen, was.

This is for my children and grandchildren who never met her, I’m sure they are curious to know Helen Klassen.

One day I will die, but I don’t want my thoughts of her to fade away, which is why I’m writing a few memories. Here is a simple tribute to the wonder that was my very own special mom. You would have loved her.

This memoir has a curious subtitle. It refers to the matter of the Ponagation. You may be wondering why the Ponagation shouldn’t be forgotten, and you may doubt if there is such a thing as a Ponagation. Put your doubts aside. The Ponagation was born, May 9th, 1927, the day my mother was born. It was ingrained in her soul, and her finger of warning wagged when she said—with furrowed brow,” Don’t forget the Ponagation.”

Mom said it solemnly, and to whomever it was said, giggles and peals of laughter would erupt. And so, it has been passed down through generations…the Ponagation, that is, the warning of not to forget it. The phrase, “Don’t forget the Ponagation,” is still heard today.

One of Four who called her Mom

My memory has become a habit. Now it doesn’t change. I remember Mom always fondly—and I can’t remember even one negative thing about her. She was about as sweet a mom as you can get. But not sweet as in spoiling sweet, just loving, and serving and caring sweet.

My name is Frieda. That means “peace.” My father liked telling me that I was the most peaceful, happy, and content baby, always ready to smile. It

was a nice thing to say and I hope it was true. In any case, I’m glad he felt that way, and glad he told me.

We were four sisters. Ruth was 2 years older, and I held her in awe. She was a hard act to follow. Bess was only a year below me, and we had a lot of common friends and hung out together. Suzy, 4 years younger than me, always played with little kids because she was a little kid.

My earliest memory of my mother is me lying on her shoulder when I’m about 2 months old. I’m wearing a sweet white baby dress that covers my whole body. Mom is supporting my body with her left arm tucked under my bottom, and her right hand is gently patting my back, as though she is trying to calm me into sleep. I feel so content and happy that I give her my killer baby smile, and she’s happy now too. We’re both happy.

Children love to look at photos of themselves as babies. They admire how cute they used to be, and if they look at the photos long enough or repeatedly, they begin to absorb the photo as a memory. That’s what I did with that 2-month-old photo of me leaning against my mother’s shoulder. I made a memory of her peering over my head, trying to see if I was asleep or just happily smiling. Yes, I remember, I was sleeping. She adored me, I’m sure.

Like her strong shoulder that cradled my big, round head, that photo became my firm foundation. Mom prided herself in strength. She was strong enough to take on babies, more babies, children and teens. But more on that later. That wasn’t all she could take pride in. She was quite talented, but very quiet about her accomplishments, unlike some other women.

She managed everything she needed to do without making a fuss. For instance, she loved kids, so on Sunday mornings, when she wasn’t teaching Sunday School, she often chose to help look after the babies in the church nursery. If she sat in the worship service, she made funny faces at the baby on the mother’s shoulder in the pew ahead of her, trying to get its attention and its smile. She was always successful. Soon I’d find myself doing the same thing. She taught me how to love babies in that way.

There was a big white plastic bottle of Johnson’s lotion at her bedside table. I remember watching her squirt and rub lots of lotion on her hands, arms,

and legs every evening. I thought it must be a something that all mothers do. But as I got older, I learned it was because she worked outside so much. Exposure to dirt, sun, and wind made her skin consistently dry. I have a clear memory of sitting beside her in church, her elbow exactly at my eye level, which I found mighty interesting. I was able to entertain myself—and sit still—while playing with the rough, dry wrinkles in her elbow. I could squish them up and down, or push this wrinkle that way, and that wrinkle this way, without her feeling a thing (or so I thought).

When we sisters began to grow, she gave us all chores. She made a chart which hung on the side of the kitchen cupboard. Our names were assigned to particular chores—there were a lot—and when the work had to be completed. Meaning every Saturday, the entire morning was spent doing chores.

I remember making a big to-do about it, moaning and whining like anything. Poor Mom. I suppose its what kids do, but she didn’t give in. We had to do the chores. There was vacuuming, sweeping, dusting, bathroom cleaning, but above all, Mom loved her gardens and her trees. So, one of the chores was to drag the garden hose all around our huge yard and water all the new trees she planted. We had five acres. There must have been one hundred, though probably closer to two hundred trees. That’s why she had to apply all the lotion.

Mom always loved us; she loved kids. She loved our friends. There was a troupe of neighbourhood girls that hung out together. We’d play dress-up together, bike together, hike together, swim together, sing and play music together, and Mom backed up all our plans. She was ever-ready to make it all happen, and often seemed to be one step ahead of us.

Once, after Suzy endlessly begged her, she secretly went to the neighbour’s house and bought their old out-house. With the help of her brother, Alden, she got it back to our house and placed it in the back yard all cleaned and painted. What a play-house! It had four walls, a roof, a door, one window, and a hole in the floor were the toilet used to be. It was perfect.

We dug through the hole in the floor to make an escape-route from attacking Indians or any bad-guys. While playing in the out-house we wore “old-fashioned clothes,” which our mother designed and sewed for us; a

long skirt, matching blouse with frills and a bonnet as well. We just loved wearing our long dresses and playing “old-fashioned days.” (It must be why I still love long skirts.)

We had the ultimate hiding-spot in our basement, a place one could never be found in a game of hide-and-go-seek. Mom got excited about it because a person of any size or age could fit into it. We called it The Disappearing Place.

One day, all of the neighbourhood kids were at our house when Uncle John showed up. Uncle John worked on the other side of the world and knew nothing about our house, so Mom decided to have some fun. Sixteen of us, including Grandpa Bohn and Mom, climbed into The Disappearing Place, and disappeared. Much to our amusement, John gave up. He was unable to find even one person.

Elated, we made a production of it, revealing ourselves one at a time as we climbed out of two partially bricked-up chimney spaces behind the wall, undetectable because of a storage space for firewood. Uncle John enjoyed all the absurdity as kid after kid appeared, and laughed harder when Mom and Grandpa tumbled out.

If we needed to get somewhere, Mom would drive us in the family station-wagon. Every Saturday night she drove us and all the neighbourhood kids

to the YMCA for recreational swimming. She would drive us there in the worst winter weather, because she liked swimming, too. After swimming, we loved stepping outside into the freezing air with our wet hair, because it instantly froze, and we could “crack” our bangs.

Back in the car, we’d drive to McDonalds for burgers and fries. It was great. Mom enjoyed it as much as we did. She loved swimming, and she also loved pickles. Every kid hated the pickles in their burgers, so she got them all.

As a kid, Mom prided herself in her strength, and it carried over into her adult years. She was quite good at Indian arm wrestling. I felt that I also inherited her strength. Because she had a steel grip, I was inspired to work on mine until I was on par with Mom. No one could out do her—or me—in a handshake that was tight as a vice and able to outlast any challenger. This was serious business, so when I came home from school, I’d search for Mom, ready to give her a handshake. Two vice-grips together made for pretty powerful stuff. No hugs, no kisses, just a hand-shake and two satisfied people. It meant everything to me.

Once, approaching Christmas, Mom organized an opera, putting it together all by herself! Although she had lots of help, she was the director and producer. All of us, my sisters, and our neighbourhood friends, had parts in it. That was really amazing because the cast was mainly scripted for adults.

However, this opera, Amahl and the Night Visitors, had children’s parts as well, with a child actually having the lead role.

We, her daughters, like everyone else, had to audition I auditioned along with all my friends for the lead role, but Mom didn’t pick us. She chose Jolene, my cousin, for the part of Amahl because Jolene could sing really high. It made sense, so we didn’t mind.

The rest of us got to be dancers. I had a special part with my friend, Chris. We did our impression of Russian Cossack dancing, dipping into low squats with our arms crossed in front of us as we bounced on bent knees with alternating kicks.

The performance was held inside the sanctuary of the Mennonite Seminary, and the place was packed. The opera was the first of its kind in our community and created a sensation. It was magical to bring alive the story of Amahl, a boy only able to walk with a crutch, and who, by the finale, finds himself at the manger of Jesus, where he receives a miracle. When he leaves baby Jesus, he is walking without a crutch. That story has always remained in me. I liked it then and like it now. Jesus’ love.

It was only a year later that my mother packed out the Seminary again. There wasn’t enough standing room left, and not everyone who came could get into the building. Many stood outside. That was Mom’s funeral service.

The amount of people who attended was significant, beyond counting. So many people gathered at the grave site for the burial that we sisters became separated from our father. Someone noticed us standing far away, took our hands, and guided us through the crowd to the front where the casket was. I don’t think Dad even realized we were missing—his grief was overwhelming.

All those people, the crowd, was a profound declaration of the specially loved person that Mom was. I’m so proud that she was my mom.

Her death was never meant to be the memorable part of her life, though it was sensationalized in the news for weeks on end, through radio broadcasts and in the newspaper. Her murder was illuminated because her life—and the manner of her death—were polar opposites. Constantly barraged with that horrible news seemed an unbelievable and impossible ending to the life of our sweet mother.

We were four daughters. Ruth, Bess, Frieda and Suzy. In my recollection, Ruth was the prettiest and the most popular and had a ton of boys following her around. Bess was a cheerleader, which Mom didn’t encourage, and Bess had her own unique popularity. Bess played clarinet very well, and Mom loved that. Mom always supported music endeavours, and in fact, enforced them. We all had to learn the piano, and after that we could choose an instrument. Ruth chose flute, so I did too. Bess played clarinet, and Suzy ended up with a violin, because there was one available. We all played recorder, and did lots of duets; Mom on tenor, me on alto, Bess on soprano.

I hated the piano lessons, but loved playing piano. I made up songs and could sit at the piano for hours. My piano teacher picked horrible songs for me to learn. Finally, she picked Bach, which I loved. Every day after school I’d sit down at the piano and play every piece in the Bach book. One day I told my teacher to give me more Bach, she said there was no more Bach at my level, so I held to my vow and quit. Mom already had me loving piano and music, so her mission was accomplished.

Sunday mornings meant that Mom would prepare and put a meatloaf into the oven on low heat so it would be ready when we returned from church. At that time, our family car was a little red VW bug, and we’d fight each other for who got to sit in the luggage area behind the back seat.

Sometimes, we’d meet up with Mom’s brother, my uncle Alden, also driving with his family back from church, and then the race would begin! We lived on the same road, a few houses apart, so both cars would begin speeding up. We’d yell, “Faster, Dad, go faster! You can beat him! Faster! Faster!” Of course, Mom couldn’t insist on speeding, but her fists would be clenched and in every body movement, she was urging Dad to pass Alden. She was totally backing us!

One time, as we neared our house, Uncle Alden was ahead. Instead of driving past our house and on to his house Alden mischievously pulled into our driveway to prove he’d won. But Dad was quick on the draw, and had a one last trick up his sleeve. He swerved sharply and drove across Mom’s precious lawn pulling in at the top of the driveway ahead of Alden! Mom was proud and bragging that we’d won fair and square!

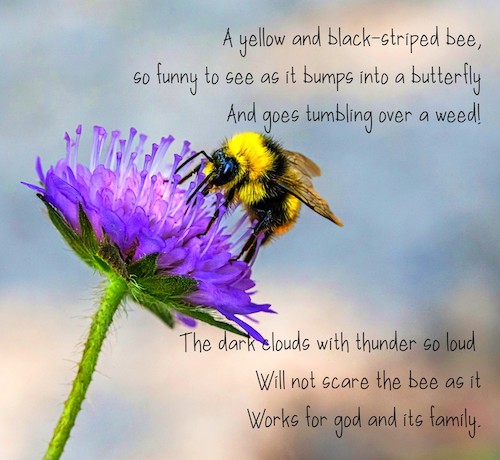

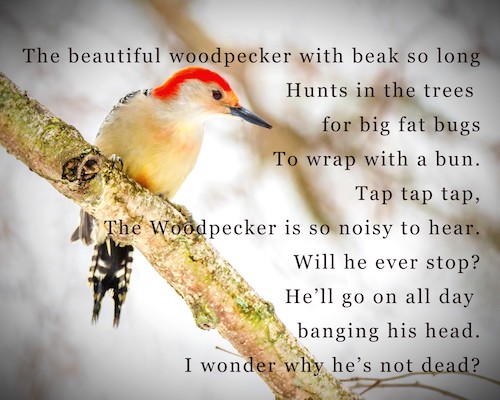

I often carted home stacks of homework. Sitting around the dining room table, Mom was our coach, helping us get through it. Whenever there was a special project, she’d be on top of it. She always knew what to do and how to help us. Once, I’d worked myself into a frenzy about an English assignment because I had to write a poem. The poem was written with Mom assisting me all the way. It was about a bird. The rhymes, the thoughts and even the drawing of the bird, full page size, was all done through the coaching of Mom. I stayed up pretty late to complete it. Mom only went to bed when she saw that I was near completion.

Another homework memory concerns a science fair project. Mom helped me narrow down some feasible topics, and I chose the ear. Mom totally emersed herself in this kind of stuff because she loved it. We (she and I) made a huge ear out of paper ma che . It turned out quite impressive and I’m sure Mom was just as proud of it as I was. It was possible to look through the ear tunnel and see every part inside, neatly labelled. I studied the ear and became knowledgeable, able to identify each part and explain its function. When the judges came around, they questioned me thoroughly and found I could answer every question.

Now, the interesting thing was, Ruth did a project on the Digestive System, and Dad (a medical doctor) helped her. She had pinned a “head” against a board that had a mouth into which liquid could be poured. The whole digestive tract was pinned there and the liquid could be watched as it travelled through every organ. Unfortunately, our projects were in the same category and we were competing against each other. That was something we hadn’t anticipated. Ruth could also answer the judges’ questions confidently. In the end, Ruth got 1st prize and I got 2nd. I was told it was because she was older. I still wonder …

During basketball season, when Ruth was a junior in high school, she was voted onto the homecoming court as an attendant to the homecoming queen. That meant during basketball half-time, the chosen attendants from each grade (girls whose roles can be likened to bridesmaids) followed the queen onto the court on the arm of their chosen escort, wearing a formal gown fit for a princess.

Ruth was a trail blazer and wore a one-strap gown with one shoulder exposed. That was crossing the line for a school kid and a Mennonite, but that was Ruth, always challenging the line. Ruth and Mom may have been soulmates in wilful-line-crossing, for it was Mom who sewed the dress that Ruth designed!

The same year Ruth was an attendant, I was also elected to be freshman attendant during football season. I had no interest in popularity, I just wanted to have fun with my best friend, Jane. One day, sitting on the bleachers together, giggling during the football pep session, my name was announced over the loudspeakers. My fear was that I was in trouble for talking, but Jane was quick to catch on, explaining that I’d been elected attendant. Then she had to explain what an “attendant” was. I was completely clueless.

Being elected was an honour, and my parents were proud—especially Mom. She didn’t make it a big celebration but quietly made it something very special for me. She took me shopping to buy the required female “suit” I had to wear while seated on the back of a convertible, holding a bouquet of flowers. She curled my hair, arranging it perfectly, and then sprayed it down till it was hurricane-proof.

I followed all the rules. The convertible was driven around the football field with us perched on the top of the back seat like royalty, smiling and waving to the crowd. Not a single hair on my head moved an inch. And I made Mom proud. For that, I’m very glad.

Three months later, I turned 15, and two weeks after that, Mom was gone.

Why was it so hard for us daughters, for Dad, and for our whole neighbourhood to recover from this tragedy? The answer is simple: no one could ever replace Mom, and there was a big hole left in everyone’s life. Such a wonderful person is irreplaceable. That must be why I rebelled when I was again elected attendant in 12th grade.

The announcement came over the inter-com while I was in class. As soon as my name was announced, I turned around in my chair to ask my cousin Steve, who always sat behind me, to be my escort—my cohort in crime. When the announcement came, I’d already concocted a plan. I told Steve he’d have to wear running shoes, jeans and an everyday shirt—not the formal suit and tie. I told him I’d wear my hiking boots, white socks, a jean

skirt, and a baggy white blouse as well. Steve had a girlfriend who was also elected to be an attendant, and she would expect him to escort her. He saw trouble ahead, but the rebellious offer was too much for him, and he immediately accepted.

We did it. When we walked onto the basketball court, there was cheering—and booing. But Steve and I were okay with it.

Why did I have to rebel? Ever since Mom died, I was fighting an unknown enemy who had stolen a priceless, irreplaceable treasure from me. I was lashing out against whatever I could, without real reason. I was angry. I was also a teenager who had no mother, and desperately needed one.

On my 12th birthday I shamelessly begged for a guitar. My parents gifted me plastic guitar (to my great disappointment) and stipulated that if I learned to play, they’d buy me a real one. I was determined and learned from Uncle

Spike. I worked out the chords for my favourite songs and began writing my own songs. Along with Bess, and our neighbourhood friends, we formed an all-girl band called Half Past (our parent’s band was called The Eleventh Hour), and played for various events. After Mom died, I sat alone, and wrote a lot of very sad songs.

The Half Past was asked to play at a mother daughter banquet. We played a song I’d written. The lyrics accused God of killing Mom. I was shaking my fist at God, singing, “What have You done! You’ve created a woman and left out the sun! I’ll be a woman still!” By the time the song was over, every mother was in tears.

Years of pain and hurt went by for our family. Confusion, grief, and death clouded everything we did. Darkness was always before us, behind us, all around us. We could not win.

The day after Mom died, after the police had collected evidence and left our house, we were allowed return home again. Relatives came from near and far. Our house was full, but Mom was not there to be the hostess. That was not right. Nothing was right. Everything was all wrong. I was sitting on the couch, squeezed into my Uncle Alden, who kept a loving hold on me. No one said much because words were empty and meaningless. And then someone voiced their thoughts aloud to Dad, a thought that seemed to be floating in everyone’s head, and in other circumstances would be considered wildly insensitive.

“You can get married again.”

The point being that without Mom, Dad could not survive. Mom was the core of all of our lives, our axis, our everything.

Her life also overflowed into many other lives as well. Children, her brothers and sisters, the church, the young boy she tutored in his studies, and who counted on her. Lots of people needed Mom. Lots of people loved Mom.

Dad remarried 4 years later, but not to someone society would have expected. In a twist that felt straight out of a movie, he married his longtime assistant, a woman who had worked beside him for years and had even known Mom. As a psychiatrist, Dad spent his life helping others. He knew how to handle people’s problems, but he could not handle losing Mom. He was lost and no one knew how to reach him, except one person. Jerrie.

Jerrie was an administrative assistant to Dad. A wheelchair user, she suffered an illness as a young woman that resulted in permanent paraplegia. Her daughter, Michelle, was five months old at the time. Her husband, unable to cope, abandoned his wife and daughter, and Jerrie became a wheelchair-bound single mom at the age of 22.

As a Mennonite, and the director of a Mennonite psychiatric clinic, Dad’s decision to marry his assistant was bound to raise eyebrows. For years, he and Jerrie maintained a strictly professional relationship, but a shift occurred after a particular moment.

That day, immersed in her administrative duties, Jerrie entered Dad’s office, assuming he wasn’t there. As she moved around his desk to leave some paperwork, she suddenly saw him—curled up beneath his desk. He was crying.

That moment marked the beginning of Jerrie’s role as more than just an assistant; she became the person who guided Dad through his deepest sorrow. She understood grief intimately, having endured her own tragedies and somehow found a way to survive. Jerrie was the right person—she was amazing.

Jerrie was 22 years old when she became paralyzed and her doctors did not think she would live. That death sentence changed when Jesus appeared in her room—she knew she would live. She did not leave the hospital for two years. She never walked again, but her drive to live was nothing short of miraculous—and live she did!

Though Jerrie’s husband abandoned her, she refused his request for a divorce for many years. Eventually, she divorced.

She had an incredible zest to live life fully. Whatever life-storm hit, and there were many, she would somehow find a way through. Her unlimited enthusiasm for life gave hope to all— Dad needed hope. We had experienced death and seemed to live with one foot in the grave. We needed her amazing drive for life so that we could LIVE and love it. She exemplified hard-core determination—just what we needed. She had known Mom, and knew what we had lost. Jerrie understood.

When they married, I had already moved out. I never lived with her. I told her, “I don’t think that I can call you Mom.” She said, “Call me anything that feels comfortable. You can call me Jerrie if you want.” I agreed to call her Jerrie, and it didn’t take long to learn what a gem she was. After a few years, I was proud to call her mom. I had two of the greatest mothers in the world. I rewrote my mom song for Jerrie, and sang it at a family reunion—it produced the same effect as the first song; everyone was in tears.

For all the Lame who Walk

Mom, you are the best

You are worthy of our respect

You are the one who has learned to face all

And stood so positive and tall.

When the weight of death hung over you.

You held on to what God could do

You held on to a love, a love so strong

That getting up to walk again seemed wrong.

A certain touch of God’s own hand

Was all that you needed to rise and stand

And so, you have stood so strong and tall

Like a mountain that cannot fall.

I’m sure you’ve been hurt and have limped along

But somehow, you’re always so tall and strong

How amazing you are in your own way

You’ve picked up the pieces from broken clay

And put them together once again

Requiring no thanks from any man

Just like Jesus became the Lamb

I know your life has been so planned.

To make you a tower of strength

While in the flesh some think you weak

May the God of peace fill you more and more

With all joy and joy restored

So that your hope will overflow

And run from your head to your toes.

May the God of peace fill you more and more

With all joy, and joy restored.

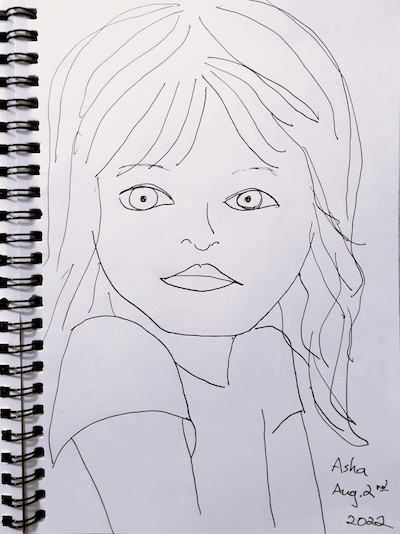

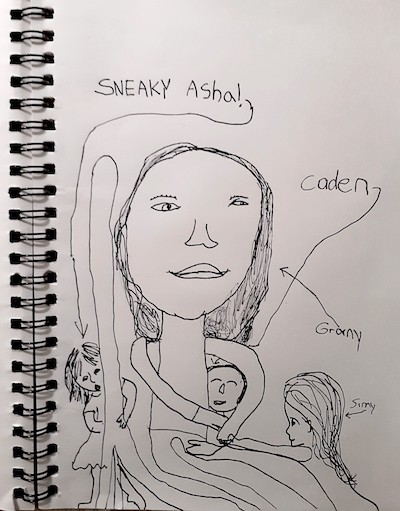

They referred to this photo as their Prom Picture—decked-up and looking ready to go… ready to take that giant step into the future. By uniting

together they were leaving the past, leaving the darkness and stepping courageously and determinedly into life and light.

We lost such a precious person in our lives. As children, it was too hard for us to talk about Mom because the pain of our grief was unbearable.

Suzy, the youngest, was the one who found Mom lifeless. She didn’t let any of us—not even Dad—share that horror. She didn’t want anyone to see what she did or to suffer as she had … a very brave, selfless little sister who was trying to protect us.

As much as we wanted to reach out and protect her, we were helpless. We needed to talk. That was what we did not do correctly. We avoided talking because of the pain. A natural response, but not a good one.

Jerrie knew she could never be the mom we kids wanted. Mom just could not be replaced. But she persevered in being all that she could be. She dealt with each of us broken pieces the best she could—not because Dad asked her too, but just because she wanted to. She, in her precarious step-mother position, loved well.

At age twenty, I fled to India for two reasons: to work with orphan children, and to escape the God who killed my mother. I knew India held many religious options.

But to my surprise, the God I was running from was already there, waiting for me.

Five months later in India, I reached the end of my road with nowhere left to go; escape from God was impossible. I needed answers.

It was midnight. I was alone in a tiny room at the children’s home in India, I broke down and told God I was done running. I wanted a truce. I wanted to be His friend. In that candle-lit darkness, Jesus entered. He met me there and we became friends. We “shook” on it—the ultimate vice-grip. A pact that would last a lifetime.

Amahl and Jerrie were healed by Jesus after they met Him. Even when I blamed God and accused Him of killing my mother, he insisted on loving me. He healed my broken life too. My seeking was done; accounts were settled… I thought.

A concerned pastor once told me I needed to forgive the man who murdered Mom. Somehow, I assumed it was “dealt with” when I made peace with Jesus. With the pastor beside me, I prayed. And in that moment… A miracle.

As I forgave, I was forgiven. I knew it immediately, for the anger in me disappeared and every wall that kept joy away fell down. It felt like a blanket of darkness had been thrown off and light was everywhere. My concern was now directed towards the murderer. He also needed the forgiving love of Jesus for his freedom. I began praying daily for him.

The greatest gift God has given me, and anyone, is the ability to talk to Him as a friend. In all my doubts, my struggles, my questions—He is for me. And was always for Mom. We are bound together, a cord of three, locked in a vice-grip. No letting go of love, and no letting go of each-other. Stronger than death.

So, now I’m talking about the funny Mom, who let her kids do funny things, and would encourage them in their plays, their dancing, all their crazy achievements, and she would act just as much of a kid as we were. If she had been given the choice, she would have stayed in Peter Pan’s Neverland forever.

This story is about my mom, Helen, but her story includes Jerrie who plays an important part. It was a complete turn-around in our story. So unexpected. But Mom would have agreed that Jerrie was someone that we and Dad needed.

And, maybe Dad was exactly what Jerrie needed too. A husband, and a father for her daughter. A missing piece neither of them had expected, but one that somehow fit just right. Dad, my sisters, Jerrie, and Michelle—we

were odd-shaped puzzle pieces in a uniquely designed picture. And somehow, we fit.

Our family turned out just the way Mom would have wanted. She’s still in the picture. Her piece is the one that holds us all together.

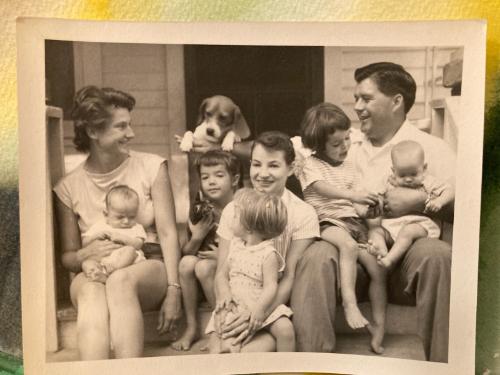

Mom is to the far left with Dad behind her. She is holding Ruth, her first-born proudly, along with the other Mennonite Moms who are sporting their babies! Fifteen years later, Ruth begged to be allowed to wear pants to church. Mom answered her pleas by sewing her a new pair of pants—Ruth was the first female to wear pants in our church!

Mom married at 21, died at 41, but she lived well—you would have loved her.

And, please, don’t forget the Ponagation.