by Dr Ann Thyle

The Doon Valley is nestled between the Shivalik hills and the lesser Himalayas. It is full of trees, hardwood, fruit, and flowering. The higher reaches of Jaunsar Bawar have deodar, spruce and pine. The tribal community, the Jaunsaris, generally work as labourers for wealthier landowners. Many attended the Herbertpur Christian Hospital for healthcare.

Early one Friday morning, the day when pre-natal patients were seen, I was waiting impatiently for the first of many patients who would trickle in from their villages. I was 36 weeks pregnant with our third child, tired and longing to go home. Discontent churned in my mind. I shouldn’t be sitting in a tiny hospital examination room where my large stomach hit the table in front of me every time I got up or leant over to write notes and prescriptions. Sweat poured down my back on that muggy monsoon day. Unlike in the big city hospital where I trained, I was the only woman doctor in this small mission hospital, seeing all the women patients, day after day, with no chance to think about my own comfort. I was cross about the prevailing culture where men would not allow a male doctor to examine their womenfolk, regardless of sometimes life-threatening conditions.

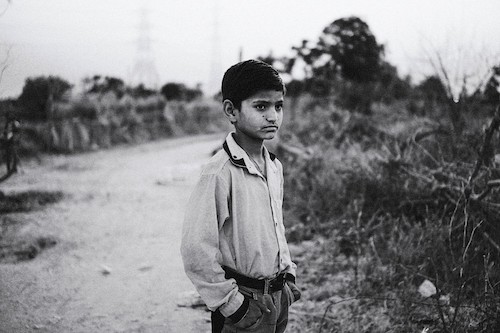

Just then, the sound of a hospital trolley being quickly wheeled in, drew my attention. There lay an unconscious, pregnant Jaunsari tribal woman in her traditional costume, a voluminous but torn ‘ghagra’ (skirt), her head covered in a skewed ‘dhantu’ (scarf). The trolley was followed closely by a man in a soiled kurta/pyjama with a ‘topi’ (hat). Clinging to him were two young, bedraggled children, ages 5 and 3-years-old. Their matted hair was a dull yellow hue, their limbs were stick-like, and their abdomens bloated—the marks of malnutrition.

I shuddered to think what their story might be.

Sharda (name changed) lived in a small village in the hills. A place without motorable roads. She belonged to the lowest caste, the ‘Doom’, also known as Dalits (untouchables). Her husband worked as a labourer in the fields of landowners, ‘the zamindars’. Sharda (26) had two children and was now pregnant with her third. Being uneducated with little knowledge of the outside world and no health facility nearby, Sharda never had a pre- natal check-up.

Sharda’s day started with her normal routine of climbing a tree to gather firewood for her mud-stove so she could make tea for her husband and start cooking breakfast. With no running water, she climbed as quickly as possible so that she could fit in a trip to the village well and draw water before the children woke up. She was unaware that she was standing on a cracked branch and had no recollection of plunging to the ground. Finding that Sharda was gone for longer than usual, her husband rounded up neighbours to help search. Her crumpled, unconscious figure lay under a tree close to their home.

I would only get the full sequence of events almost a week later.

I could imagine her husband panicking. Was Sharda alive? What about the unborn baby? How was he to get her to the nearest health facility? Where was it anyway? And how far? Neighbours rallied, placed her body in a ‘hammock’ made of a thick woollen sheet and carried her for 4 hours before reaching the hospital, a place they were told, was known for providing compassionate care. All the while she was completely unresponsive. They took turns carrying the children also.

My eyes misted over as I examined her. Guilt washed over me. An hour earlier I had grumbled about my ‘misfortune’. What greater insult could there be than to gather firewood at crack of dawn every single day, pregnancy notwithstanding, always stepping up for family who didn’t really notice, no contact with the vast world outside and a myriad of things besides. I was so privileged just by virtue of the family I was born into, my idyllic childhood, my education, my present circumstances.

She had a closed head injury, maybe a concussion, maybe a bleed. Her husband pleaded with me as I explained that we didn’t have the equipment needed to find out. Moved by his plight, the out-patient staff encouraged me, “We’ll pray for her, Doctor-ji, the baby is alive, they’re very poor. God will heal her”. In the ward, she lay unconscious for two days before going into labour. She didn’t wake with the pain, the delivery, or the cry of her new born son. For the next several days, the nurses and ward aides held the baby near her to feed, cleaned and dressed him, and we all cuddled him. Her husband and young children found place in the ‘Dharamsala,’ an area near the maternity ward designated for relatives. Other village folk shared their food. Several staff donated clothes and toys.

Most essentials of life were provided except that Sharda remained unconscious.

I mulled over what to do. We had no phones or communication systems whereby I could consult a neurologist. Sharda hadn’t opened her eyes for a week. Did she have permanent damage? Could it be fixed elsewhere? How long could we keep her? At the same time, it was impossible to abandon this precious family. My doubts continued as we did rounds in the ward that morning. Our small team stood around her bed and carried out our routine: Examine Sharda, cuddle the baby, engage with the family and pray together.

Then the impossible happened! The nurses were busy elsewhere and did not see Sharda open her eyes and stare in astonishment at her new-born son. The patient in the next bed alerted them, recovering from childbirth herself, but aware of her lifeless neighbour. Two nurses rushed to her bed while Sharda slowly sat up, looked around in perplexity and asked for a drink of water. She gathered her son into her arms and looked at him tenderly. By the time word reached me, Sharda’s beaming family stood around her bed, awe written on their faces. We rejoiced individually and as a team with Sharda. Her time of being unaware of the world around her was over, without any treatment, only by the outpouring of God’s mercy.

In the words of Philip Yancey, “In strange and mysterious ways, prayer incorporates the unknown and unpredictable in the outworking of God’s grace.”

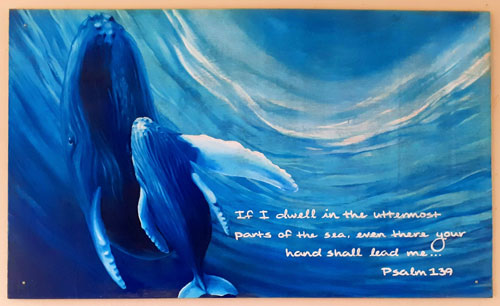

After discharge, I never saw Sharda or her family again. I imagine she climbed trees for many years to come and lived to see her children grow up and get married. I like to think that she’s being cared for by her daughter-in-law, the one married to her miracle son. That she lives in a home with power supply and running water, a place with at least a kerosene stove, if not something better. That sometimes she recounts her near-death experience to her grandchildren.

I delivered our own son a few weeks later under vastly different circumstances. By then, Sharda had taught me an invaluable lesson about contentment. My daily life had none of the challenges she faced on a regular basis. During some of my future overwhelming situations, the remembrance of Sharda showed me how fortunate I really was, the resources I could draw on, the knowledge and means to keep me steady and the all- sufficient grace of my Heavenly Father.

“I have learned in whatever situation I am to be content.” Phil 4:11

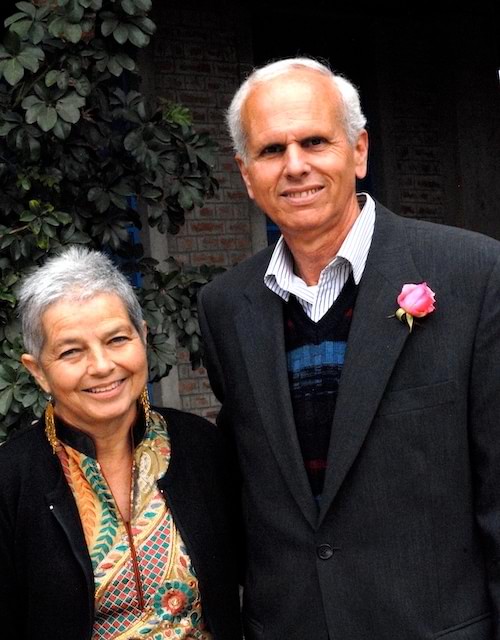

A word about Ann:

She is my friend, and more than a friend. She and her husband, also a doctor, have served our family with love. They practiced in hospitals in rural north India all of their working lives. She has many, many more stories. I, along with countless others, have valued her skills, and her heart. Thank God for servant doctors—like the Thyles.