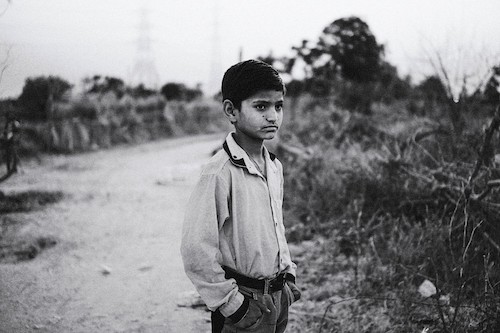

Juni spent all night crying into his pillow and devising his escape plan. He was drastically homesick. His mother dropped him at the school campus where he lived 11 months of the year with 11 other boys. Juni, 12 years old, had been part of the hostel for nearly 4 years and enjoyed the other boys, ranging 5 to 18 years old. But that night his pillow grew soggy. Every tear brought memories of his mother who lived in a crowded colony of rag-pickers along the city’s railway tracks. For Juni, “home” is “Mom.” The ghetto filth, the abusive language and life, the violence and poverty are all accepted parts of the “home” he loves. He missed her, even though her last, loud, scolding words to his hostel parents were, “Next year I’m not taking him home for the summer. He’s way too much trouble.”

Four years earlier, Juni’s father was drinking with his neighbours. Then the inevitable happened. Obscene language echoed in the narrow streets. Shouting and the sounds of rioting were heard. Suddenly, inebriated neighbours converged on him, beating Juni’s father mercilessly.

The reason? Money. Always money, debt, or greed. But that wasn’t the end for Juni’s father. A rope was tied around his neck and he was hung. When it happened, Juni and his mother were on a bus heading to Punjab to visit relatives. When the phone call came, detailing his father’s death, their journey ended. Juni and his mother turned around and went back. Juni was seven years old—old enough to have learned survival skills in the ghetto.

Juni grew up hearing conversations about money and understood money was life’s priority. Money meant survival. And he knew more than one way to earn money. At six, he would often board newly arrived trains to clean the floors, disposing of the garbage people thoughtlessly scattered during their journey. He was given a small sum for his cleaning. Juni learned what kind of trash would sell—the work of a rag-picker. Depending on what he found, or what he could steal, he could make a fair amount of money. This work was always done in the early morning hours, before dawn, in darkness, when it was easier to avoid the police. And then there was the chai shop where he could earn honest money serving chai and washing pots and cups. Juni was still a child, but he knew a lot about survival. He knew how to keep safe, and who to avoid. Which is why his escape was so perfectly planned.

When Juni’s father died, his mother was left without a way to care for her young son and work as well. She was well aware of the trouble Juni would get himself into if she was not with him. From neighbours she heard about our school and admitted him when he was eight years old. She wanted him to have a bright future.

After that night of tears, Juni appeared ready for the usual Sunday meeting at 10:00 a.m., Juni, the school staff, and the other hostel boys, had returned from a month of being with their families. In a large room everyone gathered for a time of sharing. A special activity was always planned for the children, but this Sunday included a snack for everyone as well. The younger children were excused for their activity, and it was at that precise moment that Juni’s plan kicked into action.

Before the Sunday meeting began, Juni asked a few boys for money. Then he placed a few things in his bag, including the goodies he’d recently brought from home. Early in the morning he hid the bag among some bushes. When the children were called for their activity, Juni turned into the bathroom. Who would question that? His teacher wasn’t aware that he was absent. Juni waited in the stall until there was silence, then slipped out. Ducking beneath windows where he knew adults sat, he headed for his bag in the bushes. Without slowing down, he slung it onto his back. It was 4 kilometres to the bus stop and he never stopped running. When the bus appeared at the same time he reached the stop, he scrambled aboard.

Back at the school campus, the Sunday morning meeting went on longer than usual because of a special after-meeting snack. Finally, Juni was discovered to be missing. His house-parents plopped themselves into the chairs in front of Yip and I. It was obvious from their faces that something was wrong.

“Juni has run away!” And before we could respond, “We just had a call from his mother who is asking, ‘Why is Juni at home?’”

“What? He’s already home!” I was astonished.

Slowly, the pieces began to fit together.

Juni had been a ringleader in the younger boy’s hostel. He planned what they could steal from the school and how it would be done. Biscuits, cell phones, and purses began disappearing. He’d observed what items there were on the campus, including the trash, and decided what could be sold to earn a little money. With the younger boys enlisted to help, they started collecting trash, and even did some stealing. And finally, Juni taught them how they could successfully avoid detection while breaking rules and running away. He told them the plan of his great escape and asked them, “Who wants to come with me?” He had no followers. They’d been punished before because of Juni’s escapades.

He left undetected. His plan was a success. From the time of the children’s activity until the snack afterwards, Juni had travelled home. He’d run 7 kilometres, and rode 34 kilometres on the bus to the city. Juni knew how to survive. He knew how to succeed.

Our immediate thought was to get Juni back and help him to understand that the school where he learns is for his benefit, for his success. It may not be “home,” but is a place that offers him and his mother a positive, alternative chance in life. We wanted him to understand that he could learn to navigate, and achieve success in a world that demands education. He could succeed in a career and be able to provide for his mother. He would be able to get her out of the ghetto. But that didn’t happen.

Juni’s mother sided with her son, believing his lies of being mistreated… Or why would he run away? She threatened us: If her son returned to the hostel, and attempted to run away again, she’d hold us accountable if he didn’t make it home. She declared loudly, “I lost my husband, and now can’t face the possibility of losing my son as well.”

Knowing Juni’s proclivities, we had to let go. “Mom,” is universal for “home.” Wherever Mom is, the heart is. The ghetto filth, the abusive life, the violence and poverty are all part of the “home” Juni loved. We had to trust God for Juni who wanted to fit into his dad’s shoes and care for his mother. He had executed his escape plan faultlessly, but could he survive in a place where his dad couldn’t?

We will remember Juni’s tears, and pray.